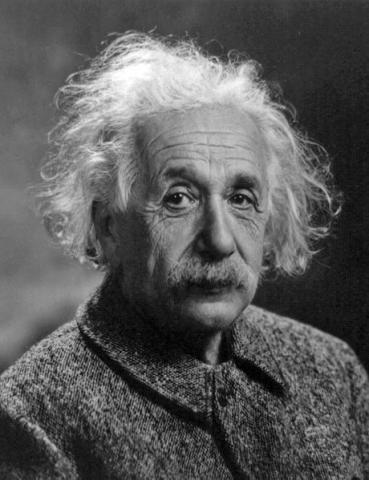

Obrázek: cs.wikipedia.org

Alberta Einsteina se často dovolávali jak ateisté, tak i věřící. Bylo to umožněno komplikovanou vírou a pohledem na svět, který Einstein jako vědec měl, neméně také tím, že názory během svého života občas změnil. Snad s určitou mírou jistoty se dá říct velmi stručně, že Einstein nikdy v celém svém životě nepřipustil, že by byl ateista. Určitě se necítil být křesťanem; o postavě Ježíše se vyslovoval uctivě a uznával Ježišovu historicitu. Nicméně o Starém zákoně se vyjadřoval s despektem, od judaismu se velmi brzo ve svém životě odklonil.

Aby si čtenář mohl udělat vlastní úsudek, následuje něco málo z Einsteinova smýšlení. Upozorňuji, že první příběh „Zlo neexistuje…“ má mnoho různých verzí a nemám zjištěno, zda jde o autentický příběh.

Zlo neexistuje

Pan profesor na univerzitě položil svým studentům otázku:

Je všechno, co existuje, stvořené Bohem?

Jeden ze studentů nesměle odpověděl: Ano, je to stvořené Bohem.

Stvořil Bůh všechno? – ptal se dál profesor.

Ano pane, odpověděl student.

Profesor pak pokračoval: Jestli Bůh stvořil všechno, znamená to, že Bůh

stvořil i zlo, které existuje. A díky tomuto principu, naše činnost určuje

nás samotné. Bůh je tedy zlo.

Když toto student vyslechl, ztichl. Profesor byl sám se sebou spokojený.

Najednou zvedl ruku jiný student.

Pane profesore, mohu Vám položit otázku?

Samozřejmě, odpověděl profesor.

Student se postavil a zeptal se: Existuje chlad?

Co je to za otázku, samozřejmě že ano, tobě nikdy nebylo chladno?

Studenti se zasmáli otázce spolužáka, ale ten pokračoval: Ve skutečnosti

pane, chlad neexistuje, v souladu se zákony fyziky je chlad

pouze nepřítomnost tepla. Člověka a předměty můžeme popsat a určit

jejich energii na základě přítomnosti anebo tvorby tepla, ale nikdy ne na

základě přítomnosti či tvorby chladu. Chlad nemá svoji jednotku, kterou

ho můžeme měřit. Slovo chlad jsme si vytvořili my lidé, abychom mohli

popsat to, co cítíme v nepřítomnosti tepla.

Student pokračoval: Pane profesore, existuje tma?

Samozřejmě, že existuje – odpověděl profesor. Znovu nemáte pravdu, tma

neexistuje. Ve skutečnosti je tma jen díky tomu, že není přítomno světlo.

Můžeme zkoumat světlo, ale ne tmu. Světlo se dá rozložit. Můžeme zkoumat

paprsek za paprskem, ale tma se změřit nedá. Tma nemá svoji jednotku, ve

které bychom ji mohli měřit. Tma je jen pojem, který si vytvořili lidé, aby

pojmenovali nepřítomnost světla.

Následně se mladík zeptal: Pane, existuje zlo? Tentokrát profesor nejistě

odpověděl:

Samozřejmě, vidíme to každý den, brutalita ve vztazích mezi lidmi, trestné

činy, násilí, všechno toto není nic jiného, než projev zla.

Na to student odpověděl: Zlo neexistuje, pane. Zlo je jen nepřítomnost

dobra, tedy Boha. Zlo je výsledek nepřítomnosti lásky v srdci člověka. Zlo

přichází tak, jako když přichází tma, nebo chlad – tedy v nepřítomnosti

světla, tepla a lásky.

Profesor si sedl.

Ten student byl mladý Albert Einstein.

Einstein a jeho víra

Daniel Raus

28. 5. 2007

Tento český překlad je jen spíše volným převyprávěním níže uvedeného anglického originálu článku Waltera Isaacsona Einstein & Faith, který je zkopírován pod tímto českým textem.

Jak to bylo s Einsteinem a jeho vírou? Touto otázkou se zabývá na svých internetových stránkách časopisu Time. Název článku zní příznačně: „Einstein a víra“ a jeho autorem je Walter Isaacson, který konstatuje, že pro většinu lidí slouží zázraky jako důkaz Boží existence. Pro Einsteina byla spíše jejich absence dokladem nadpřirozena. Skutečnost, že svět funguje racionálně, podle zřejmých zákonů, to pro něj byl důvod k údivu.

Albert Einstein se jako dítě moc neměl k mluvení. Jednou dokonce vzpomínal na to, jaké starosti si dělali jeho rodiče, takže se radili s lékařem. Pomalý vývoj v tomto směru byl kombinovaný s rebelií vůči autoritám, takže jeden ředitel školy ho vyloučil a další mu prorokoval, že v životě ničeho nedosáhne. To udělalo z Einsteina navždy patrona všech problematických dětí kdekoliv na světě.

Právě problém s autoritou ho vedl k tomu, že si kladl otázky, nad kterými akademici nikdy nemeditovali. A pomalý vývoj ve verbální oblasti mu zase umožňoval pozastavit se nad každodenními věcmi, kterých si jiní ani nevšimli. Místo toho, aby obdivoval mystické záhady, obdivoval samozřejmosti.

Později řekl: „Když se mě lidé ptají, jak jsem se vlastně dopracoval k teorii relativity, zdá se mi, že se to stalo takhle: Běžně se dospělý člověk vůbec nezabývá problémem času a prostoru, protože se o nich naučil všechno už jako dítě. Já jsem se ale vyvíjel tak pomalu, že mě začal zajímat prostor a čas, až když jsem byl dospělý. Tak jsem do toho šel prostě hlouběji, než jak by do toho šlo běžné dítě“.

S odstupem času se zdá být logické, že kombinace úžasu a rebelského postoje učinila z Einsteina mimořádného vědce. Co je ale méně známé, je to, že tato dvojkolejnost jeho vývoje silně ovlivňovala také jeho víru. Nejdříve odmítl sekularismus svých rodičů, později koncept náboženských rituálů a koncept osobního Boha, který zasahuje do každodenních záležitostí člověka. V padesáti letech ho ale pojal úžas, který ho vedl k deismu a k přesvědčení, že „duch se projevuje ve vesmíru“ a „Bůh se projevuje v harmonii všeho, co existuje“.

Einstein byl ze strany obou rodičů potomkem židovských obchodníků, kteří žili skromně po dvě staletí na jihozápadě Německa. S každou generací se víc a víc asimilovali v tamní společnosti, kterou milovali – nebo si alespoň mysleli, že ji milují. Co se týče náboženství, neměli o něj velký zájem. Ve svých dopisech zmiňoval Einstein vtip o nevěřícím strýci, který chodil jako jediný z rodiny do synagogy – a na otázku, proč to vlastně dělá, odpovídal slovy: „nikdy nevíš“. Rodina ale neměla s náboženstvím prakticky nic společného.

Albert se ale z ničeho nic začal zajímat o judaismus. Začal dodržovat striktní předpisy. Jak popisovala později jeho sestra, nejedl vepřové maso, všechno muselo být „košer“ a světil sobotu. Skládal si dokonce vlastní náboženské písně, které si prozpěvoval cestou ze školy. Největší stimulací pro něj byl chudý student medicíny Max Talmud, který chodil k Einsteinovým každý čtvrtek.

Byla to určitá tradice, že se židovské rodiny měly starat o chudé. Einsteinovi si ji přizpůsobili tak, že pravidelně zvali domů tohoto studenta. Bylo mu 21 a Albertovi bylo 10. Talmud nosil Albertovi knihy o vědě, a ten je pak četl se zatajeným dechem. Uvedl ho také do tajů matematiky. Malý Einstein mu pak každý čtvrtek ukazoval, co vyřešil – a brzo předběhl svého „učitele“. Když mu bylo dvanáct, opustil judaismus. Nebylo to ale kvůli vědeckým knihám, protože mezi náboženstvím a vědou neviděl žádný konflikt.

Až když mu bylo padesát, začal se vyjadřovat k víře v různých článcích, rozhovorech a dopisech. Jeho verze víry byla neosobní. V roce 1929 byl se svou manželkou u jakýchsi hostitelů v Berlíně. Jeden z hostů začal mluvit o své víře v astrologii. Einstein se tomu vysmál jako čiré pověrčivosti. Další host se podobným způsobem začal vyjadřovat i o náboženství.

Hostitel ale poznamenal, že samotný Einstein se kloní k víře, což vyvolalo překvapení. A Einstein prohlásil: „Když se snažíte pronikat našimi omezenými prostředky do tajů přírody, zjistíte, že za zřejmými zákony a souvislostmi existuje něco velmi jemného, neuchopitelného a nevysvětlitelného. Úctu k této síle, jež se za vším skrývá, můžeme označit za moje náboženství. V tomhle smyslu jsem tedy náboženský“.

Těsně po svých 50. narozeninách poskytl Einstein pozoruhodný rozhovor o nacionalismu a víře. Na otázku, zda ho ovlivnilo křesťanství, odpověděl: „Jako dítě jsem byl vychováván na Bibli i na Talmudu. Jsem Žid, ale zářivá postava z Nazareta mě fascinuje“. Následovala otázka, zda si myslí, že Ježíš byl historickou postavou. Einstein odpověděl: „Nepochybně ano. Nikdo přece nemůže číst evangelia bez toho, aby cítil přítomnost Ježíše. Jeho osobností přece pulzuje každé slovo. Žádný mýtus není takhle naplněn životem“.

Další otázka tedy zněla, zda věří v Boha. Einstein odpověděl: „Nejsem ateista. A myslím, že se nemůžu označit za panteistu.. Je to otázka, jež je příliš široká pro naši omezenou mysl. Jsme jako malé dítě, vcházející do obrovské knihovny, přeplněné knihami v nejrůznějších řečech. Dítě ví, že někdo musel ty knihy napsat, ale neví, jak je napsal. Nerozumí řečem, ve kterých jsou knihy napsané. Matně tuší jakýsi nadpřirozený pořádek v tom, jak jsou knihy uspořádané, ale nic o něm neví. Takové je podle mě postavení i toho nejinteligentnějšího člověka vůči Bohu“.

Einstein byl během celého života naprosto konzistentní v odmítání nařčení, že je ateista. Dokonce ho rozčilovalo, že ho ateisté citovali ve svých argumentacích. Nikdy nepociťoval potřebu snižovat něčí víru, ale v případě ateistů tuto tendenci měl. Jednou prohlásil: „Rozdíl mezi mnou a většinou takzvaných ateistů je pocit naprosté pokory před neuchopitelným tajemstvím a harmonií kosmu“.

Přibližně do těchto míst je převyprávěn výše uvedený český text

Is this a Jewish concept of God? „I am a determinist. I do not believe in free will. Jews believe in free will. They believe that man shapes his own life. I reject that doctrine. In that respect I am not a Jew.“

Is this Spinoza’s God? „I am fascinated by Spinoza’s pantheism, but I admire even more his contribution to modern thought because he is the first philosopher to deal with the soul and body as one, and not two separate things.“

Do you believe in immortality? „No. And one life is enough for me.“

Einstein tried to express these feelings clearly, both for himself and all of those who wanted a simple answer from him about his faith. So in the summer of 1930, amid his sailing and ruminations in Caputh, he composed a credo, „What I Believe,“ that he recorded for a human-rights group and later published. It concluded with an explanation of what he meant when he called himself religious: „The most beautiful emotion we can experience is the mysterious. It is the fundamental emotion that stands at the cradle of all true art and science. He to whom this emotion is a stranger, who can no longer wonder and stand rapt in awe, is as good as dead, a snuffed-out candle. To sense that behind anything that can be experienced there is something that our minds cannot grasp, whose beauty and sublimity reaches us only indirectly: this is religiousness. In this sense, and in this sense only, I am a devoutly religious man.“

People found the piece evocative, and it was reprinted repeatedly in a variety of translations. But not surprisingly, it did not satisfy those who wanted a simple answer to the question of whether or not he believed in God. „The outcome of this doubt and befogged speculation about time and space is a cloak beneath which hides the ghastly apparition of atheism,“ Boston’s Cardinal William Henry O’Connell said. This public blast from a Cardinal prompted the noted Orthodox Jewish leader in New York, Rabbi Herbert S. Goldstein, to send a very direct telegram: „Do you believe in God? Stop. Answer paid. 50 words.“ Einstein used only about half his allotted number of words. It became the most famous version of an answer he gave often: „I believe in Spinoza’s God, who reveals himself in the lawful harmony of all that exists, but not in a God who concerns himself with the fate and the doings of mankind.“

Some religious Jews reacted by pointing out that Spinoza had been excommunicated from Amsterdam’s Jewish community for holding these beliefs, and that he had also been condemned by the Catholic Church. „Cardinal O’Connell would have done well had he not attacked the Einstein theory,“ said one Bronx rabbi. „Einstein would have done better had he not proclaimed his nonbelief in a God who is concerned with fates and actions of individuals. Both have handed down dicta outside their jurisdiction.“

But throughout his life, Einstein was consistent in rejecting the charge that he was an atheist. „There are people who say there is no God,“ he told a friend. „But what makes me really angry is that they quote me for support of such views.“ And unlike Sigmund Freud or Bertrand Russell or George Bernard Shaw, Einstein never felt the urge to denigrate those who believed in God; instead, he tended to denigrate atheists. „What separates me from most so-called atheists is a feeling of utter humility toward the unattainable secrets of the harmony of the cosmos,“ he explained.

In fact, Einstein tended to be more critical of debunkers, who seemed to lack humility or a sense of awe, than of the faithful. „The fanatical atheists,“ he wrote in a letter, „are like slaves who are still feeling the weight of their chains which they have thrown off after hard struggle. They are creatures who–in their grudge against traditional religion as the ‚opium of the masses‘– cannot hear the music of the spheres.“

Einstein later explained his view of the relationship between science and religion at a conference at the Union Theological Seminary in New York. The realm of science, he said, was to ascertain what was the case, but not evaluate human thoughts and actions about what should be the case. Religion had the reverse mandate. Yet the endeavors worked together at times. „Science can be created only by those who are thoroughly imbued with the aspiration toward truth and understanding,“ he said. „This source of feeling, however, springs from the sphere of religion.“ The talk got front-page news coverage, and his pithy conclusion became famous. „The situation may be expressed by an image: science without religion is lame, religion without science is blind.“

But there was one religious concept, Einstein went on to say, that science could not accept: a deity who could meddle at whim in the events of his creation. „The main source of the present-day conflicts between the spheres of religion and of science lies in this concept of a personal God,“ he argued. Scientists aim to uncover the immutable laws that govern reality, and in doing so they must reject the notion that divine will, or for that matter human will, plays a role that would violate this cosmic causality.

His belief in causal determinism was incompatible with the concept of human free will. Jewish as well as Christian theologians have generally believed that people are responsible for their actions. They are even free to choose, as happens in the Bible, to disobey God’s commandments, despite the fact that this seems to conflict with a belief that God is all knowing and all powerful.

Einstein, on the other hand, believed–as did Spinoza–that a person’s actions were just as determined as that of a billiard ball, planet or star. „Human beings in their thinking, feeling and acting are not free but are as causally bound as the stars in their motions,“ Einstein declared in a statement to a Spinoza Society in 1932. It was a concept he drew also from his reading of Schopenhauer. „Everybody acts not only under external compulsion but also in accordance with inner necessity,“ he wrote in his famous credo. „Schopenhauer’s saying, ‚A man can do as he wills, but not will as he wills,‘ has been a real inspiration to me since my youth; it has been a continual consolation in the face of life’s hardships, my own and others‘, and an unfailing wellspring of tolerance.“

This determinism appalled some friends such as Max Born, who thought it completely undermined the foundations of human morality. „I cannot understand how you can combine an entirely mechanistic universe with the freedom of the ethical individual,“ he wrote Einstein. „To me a deterministic world is quite abhorrent. Maybe you are right, and the world is that way, as you say. But at the moment it does not really look like it in physics–and even less so in the rest of the world.“

For Born, quantum uncertainty provided an escape from this dilemma. Like some philosophers of the time, he latched onto the indeterminacy that was inherent in quantum mechanics to resolve „the discrepancy between ethical freedom and strict natural laws.“

Born explained the issue to his wife Hedwig, who was always eager to debate Einstein. She told Einstein that, like him, she was „unable to believe in a ‚dice-playing‘ God.“ In other words, unlike her husband, she rejected quantum mechanics‘ view that the universe was based on uncertainties and probabilities. But, she added, „nor am I able to imagine that you believe–as Max has told me–that your ‚complete rule of law‘ means that everything is predetermined, for example whether I am going to have my child inoculated.“ It would mean, she pointed out, the end of all moral behavior.

But Einstein’s answer was to look upon free will as something that was useful, indeed necessary, for a civilized society, because it caused people to take responsibility for their own actions. „I am compelled to act as if free will existed,“ he explained, „because if I wish to live in a civilized society I must act responsibly.“ He could even hold people responsible for their good or evil, since that was both a pragmatic and sensible approach to life, while still believing intellectually that everyone’s actions were predetermined. „I know that philosophically a murderer is not responsible for his crime,“ he said, „but I prefer not to take tea with him.“

The foundation of morality, he believed, was rising above the „merely personal“ to live in a way that benefited humanity. He dedicated himself to the cause of world peace and, after encouraging the U.S. to build the atom bomb to defeat Hitler, worked diligently to find ways to control such weapons. He raised money to help fellow refugees, spoke out for racial justice and publicly stood up for those who were victims of McCarthyism. And he tried to live with a humor, humility, simplicity and geniality even as he became one of the most famous faces on the planet.

For some people, miracles serve as evidence of God’s existence. For Einstein it was the absence of miracles that reflected divine providence. The fact that the world was comprehensible, that it followed laws, was worthy of awe.

From Einstein by Walter Isaacson. © 2007 by Walter Isaacson. To be published by Simon & Schuster, Inc.